The Elections Performance Index Charts a Decade’s Progress in Election Administration

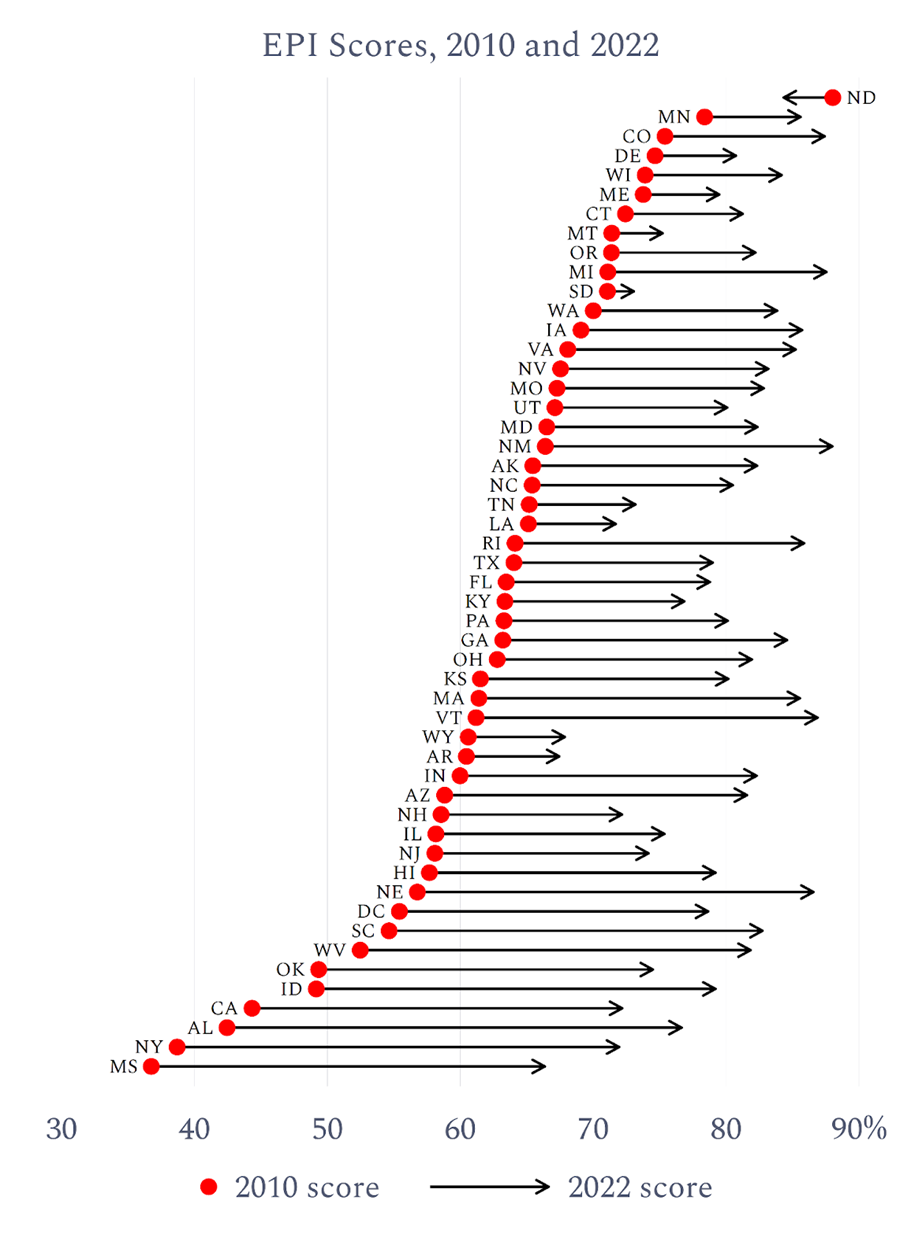

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab (MEDSL) has just released its biennial update of the Elections Performance Index, adding the 2022 election to the collection. For many people, the EPI is a chance to see which state is ranked first and which is ranked last. However, I don’t think that’s the big story. The big story is how over the past decade, the EPI has charted the steady improvement of virtually every state in how elections are administered.

First, some background. The EPI was launched by the Pew Charitable Trusts a decade ago, inspired by Heather Gerken’s book, The Democracy Index. MEDSL took it over beginning with the 2016 election.

The simple idea behind the EPI is to measure how well states perform on a variety of performance metrics that span the election administration space, both those that measure access and those that measure security. For midterm elections, such as 2022, the EPI is based on eighteen indicators, including items such as the percentage of mail ballots rejected, whether the state requires risk-limiting tabulation audits, and the turnout rate.

The indicators measure a mix of policies and how policies are implemented. Election officials, especially those in states that have relatively low scores, often interpret the EPI as casting a judgment on how well they are doing their jobs. After more than a decade of being involved with the project, I’ve come to the conclusion that’s an incorrect interpretation of the EPI. The biggest factors that influence where a state stands in the EPI index are matters of policy, such as whether they require post-election audits, or state capacity, such as whether they deploy the web for registration and communicating with voters about their ballots.

Yes, if you drill down to the data at the county level, where elections are actually conducted, some counties look better than others on the EPI indicators.

Nonetheless, localities in one state all tend to perform more similarly to each other than they do to localities in other states. We wouldn’t see these patterns if differences in the EPI index were primarily a matter of local administration.

Let’s get to the numbers. The 2022 EPI is based on eighteen indicators. (See the sidebar.) Each indicator is measured on a scale that runs from zero (worst performance across the life of the EPI) to one (best performance). All the indicators are then averaged to give each state an EPI index score. In 2010, the first midterm covered by EPI, the average score was 62.9%, ranging from 37% (Mississippi) to 88% (North Dakota). In 2022, the average had risen to 80%, ranging from 56% (Mississippi) to 88% (New Mexico).

What has changed over the past decade-plus? A lot. Breaking the EPI into its component parts, no indicator has seen a decline since 2010, and many have seen dramatic increases. For instance, in 2010, only 8 states had online registration; in 2022, that number was 42. Only 29 states required a post-election tabulation audit in 2010; 45 states did in 2022. The percentage of UOCAVA ballots unreturned fell from 53.1% in 2010 to 36.9% in 2022.

Changes in average raw values of EPI indicators, 2010 to 2022 |

|||

Indicator |

2010 |

2022 |

Notes |

|

Online registration available |

8 states |

42 states |

|

|

Post-election audits required |

29 states |

45 states |

|

|

Web voter lookup tools |

65% |

87% |

Percentage of possible tools |

|

UOCAVA ballots unreturned |

53.1% |

36.9% |

Percentage of UOCAVA ballots requested |

|

Non-voting due to reg. problems |

3.9% |

2.1% |

|

|

Provisional ballots cast |

0.95% |

0.65% |

Percentage of all votes cast |

|

UOCAVA ballots rejected |

6.7% |

3.4% |

Percentage of UOCAVA ballots returned for counting |

|

Wait time |

4 min.* |

5 min. |

|

|

Provisional ballots rejected |

0.15% |

0.13% |

Percentage of all votes cast |

|

New registrations rejected |

9.3% |

6.6% |

Percentage of new registrations received |

|

Mail ballots unreturned |

12.9% |

14.7% |

Percentage of mail ballots transmitted |

|

EAVS data completeness |

94.4% |

96.9% |

Percentage of selected statistics reported by states |

|

Voter registration rate |

79.1% |

84.4% |

Percentage of citizens |

|

Turnout rate |

43.7% |

47.5% |

Percentage of voting-eligible population |

|

Mail ballots rejected |

0.23% |

0.38% |

Percentage of all votes cast |

|

*Not measured in 2010; measurement from 2014 |

Even the few indicators that have seen a decline since 2010 have seen only a minor decline. For instance, in 2022, 14.7% of mail ballots were unreturned, up from 12.9% in 2010.

The indicators included in the EPI have remained largely unchanged since MEDSL took over the maintenance of the index with the 2016 election. There have been a few small changes, however, that have on the whole led to further national improvement in average index scores. Starting in 2020, for instance, the EPI started including ERIC membership and the requirement for risk-limiting audits in the index. They are included in a way that can increase the score of states with these policies, but they do not decrease the score of states that have not adopted them. In addition, the EPI changed how it measures non-voting due to disability to more directly measure the difference in turnout between those with and without physical disabilities.

Where will the EPI go next? MEDSL is already preparing to gather data to update the index for the 2024 election. Within the current framework of the index, we are considering measures to better measure how states clean the voter rolls and to take into account the fact that turnout is based on both policy and non-policy factors. We are following developments among the states that have left ERIC (along with those that never joined in the first place) to see whether the alternatives that have been developed match ERIC in security and effectiveness.

At the same time, it may be time to consider more than marginal changes to the EPI and consider broader changes. As it stands, almost every state has adopted policies that were emerging best practices in the late 2000s. This leaves variations in EPI scores from election to election more prone to random variation. Should the EPI evolve in a non-incremental fashion, it will be in collaboration between election officials and academicians, just as it was done a dozen years ago.

Until then, we still hope that the few states with low index scores will see them climb for 2024 and 2026. We can also hope that this year’s release of the EPI will spawn robust discussion in the community about what constitutes a well-functioning election administration and how we can tell it when we see it.